Hypothesis Testing

Introduction

Tests provide the theoretical basis for decision-making based on data. For example, doctors diagnose diseases using specific biological markers, industrial quality engineers evaluate the quality of a production batch, and climate scientists determine whether there are significant changes in measurements compared to the pre-industrial era.

General Principles

Hypothesis testing is a key statistical method that enables professionals to make informed decisions. The process involves setting up two competing hypotheses:

- the null hypothesis \(H_0\), which assumes no effect or no difference. This is usually an a priori on the data.

- the alternative hypothesis \(H_1\), which suggests that there is a significant effect or difference.

Let’s illustrate this with the example of a doctor diagnosing a disease, such as diabetes, using blood glucose levels:

- The doctor begins by assuming the null hypothesis \(H_0\): the patient’s blood glucose levels are normal, indicating no diabetes.

- The alternative hypothesis (\(H_1\)) would suggest that the patient’s glucose levels are abnormally high, indicating diabetes.

After collecting the patient’s blood glucose data, the doctor compares it to a standard threshold for diagnosing diabetes. A hypothesis test is then performed to evaluate whether the observed glucose level is significantly higher than the threshold, or whether the difference could simply be due to random variation.

The testing process can be summarized as follows:

- Fix an objective: test whether Bob has diabetes

- Design an experiment: measure of glucose level

- Define hypotheses

- Null hypothesis: \(H_0\): a priori, Bob has no diabetes

- Alternative hypothesis: \(H_1\): Bob has diabete

- Define a decision dule: function of the glucose level

- Collect data: do the measure of glucose level

- Apply the decision rule: reject \(H_0\) or not

- Draw a conclusion: should Bob follow a treatment or make other tests?

Good and Bad Decisions

| Decision | \(H_0\) True | \(H_1\) True |

|---|---|---|

| \(T=0\) | True Negative (TN) |

False Negative (FN)

|

| \(T=1\) |

False Positive (FP)

|

True Positive (TP) |

In general, observing \(T=1\) is just one piece of evidence supporting \(H_1\). It’s possible that we were simply unlucky and the data led the test to reject \(H_0\). Additionally, the sample used might not be representative, or the elevated glucose level could be caused by another condition, not diabetes. Therefore, we cannot blindly accept \(H_1\) based on this result alone. Further investigation is essential when \(T=1\) to minimize the risk of making a Type I error.

The same applies when \(T=0\). A result of \(T=0\) simply indicates that the test provides no evidence in favor of \(H_1\), but it doesn’t mean that \(H_1\) is false. It is possible that the patient exhibits other symptoms that could still suggest a diagnosis of diabetes, despite the lack of evidence from the test.

Examples

Dice biased toward \(6\)

- Objective: test if Bob is cheating with a dice.

- Experiment: Bob rolls the dice \(10\) times.

- Hypotheses:

- \(H_0\): the probability of getting \(6\) is \(1/6\)

- \(H_1\): the probability of getting \(6\) is larger than \(1/6\)

- Decision rule: the probability of getting a number of \(6\) at least equal to the number of observed \(6\) is \(< 0.05\)

- Data: the dice falls \(10\) times on \(6\)

- Decision: the probability is \(1/6^{10} < 0.05\)

- Conclusion?

In the above example, we formally observe \((X_1, \dots, X_n)\) iid where \(X_i \in \{1, \dots, 6\}\) where each \(\mathbb P(X_i = k) = p_k\) Imagine that instead of ten \(6\), we observed \(600\) tosses leading to the following counts:

The number of \(6\) is really close to \(100 = 600/6\), which implies that we would not reject \(H_0\) in the previous example. We would reject however if we wanted to test whether the dice is fair, since it is highly biased toward \(2\).

- \(H_0: p_6 = 1/6\) VS \(H_1: p_6 > 1/6\)

- Do not reject \(H_1\) (\(H_0\) is “likely”)

- \(H_0: (p_1=\dots=p_6 = 1/6)\) (dice is fair) VS \(H_1: \exists k: p_k > 1/6\)

- Reject \(H_1\) (\(H_0\) is “unlikely”)

Medical test

See also the (Pluto notebook: illustration of pvalue)

- Objective: test if a fetus has Down syndrome

- Experiment: measure the Nucal translucency

- Hypotheses:

- \(H_0\): nucal translucency is normal \(\sim \mathcal N(1.5,0.8)\)

- \(H_1\): nucal translucency is large

- Decision rule: reject if \(P_0(X \geq x_{obs}) \leq 0.05\) (“\(95^{th}\) percentile”)

- Collect data: \(x_{obs}=3.02\)

- Make a decision: Calculate the value of \(P_0(X \geq 3.02)=0.029\)

- Conclusion?

Basics of Hypothesis Testing

Estimation VS Test

- We observe some data \(X\) in a measurable space \((\mathcal X, \mathcal A)\).

- Example \(\mathcal X = \mathbb R^n\): \(X= (X_1, \dots, X_n)\).

Estimation

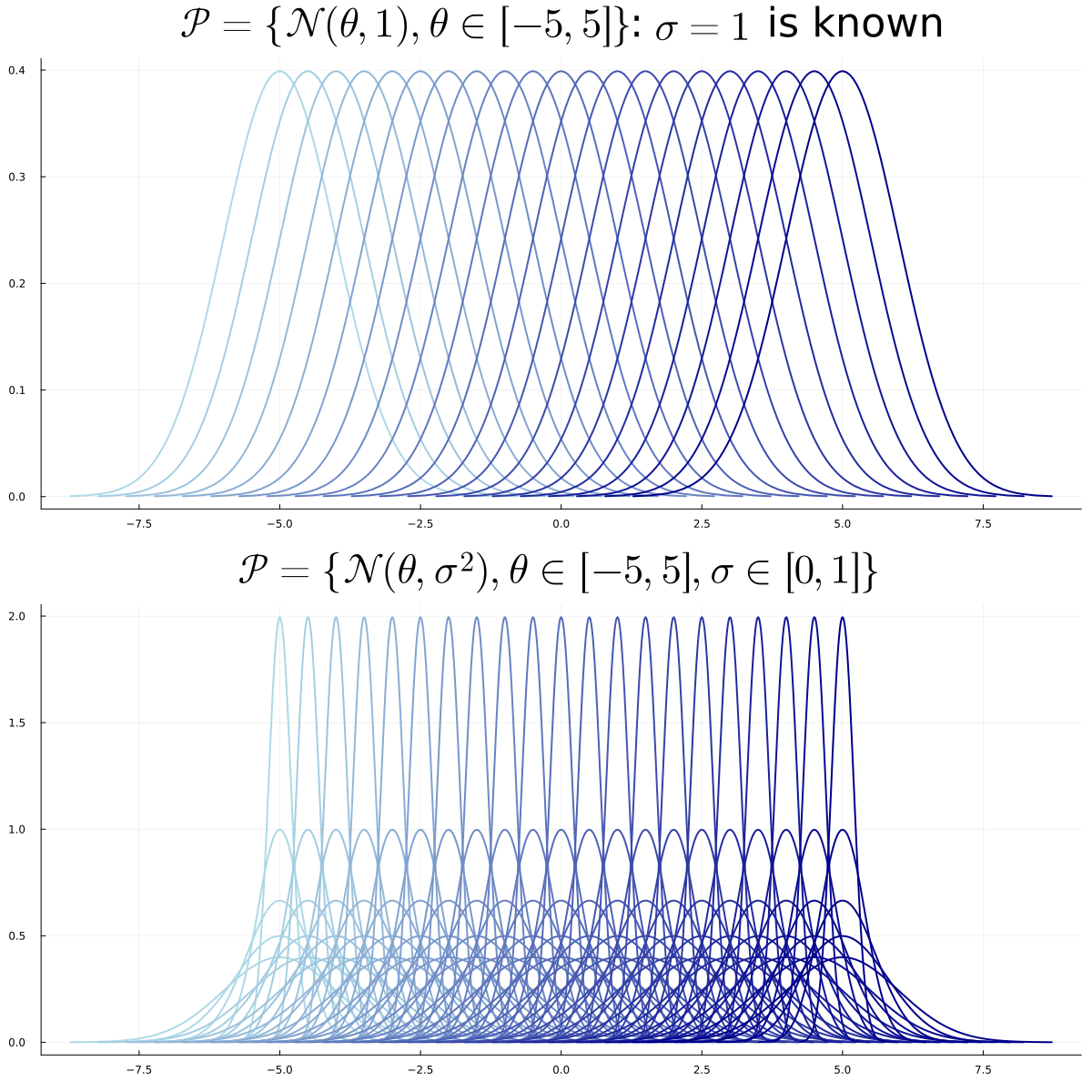

- One set of distributions \(\mathcal P\)

- Parameterized by \(\Theta\) \[ \mathcal P = \{P_{\theta},~ \theta \in \Theta\} \; . \]

- \(\exists \theta \in \Theta\) such that \(X \sim P_{\theta}\)

Goal: estimate a given function of \(P_{\theta}\), e.g.:

- \(F(P_{\theta}) = \int x dP_{\theta}\)

- \(F(P_{\theta}) = \int x^2 dP_{\theta}\)

Test

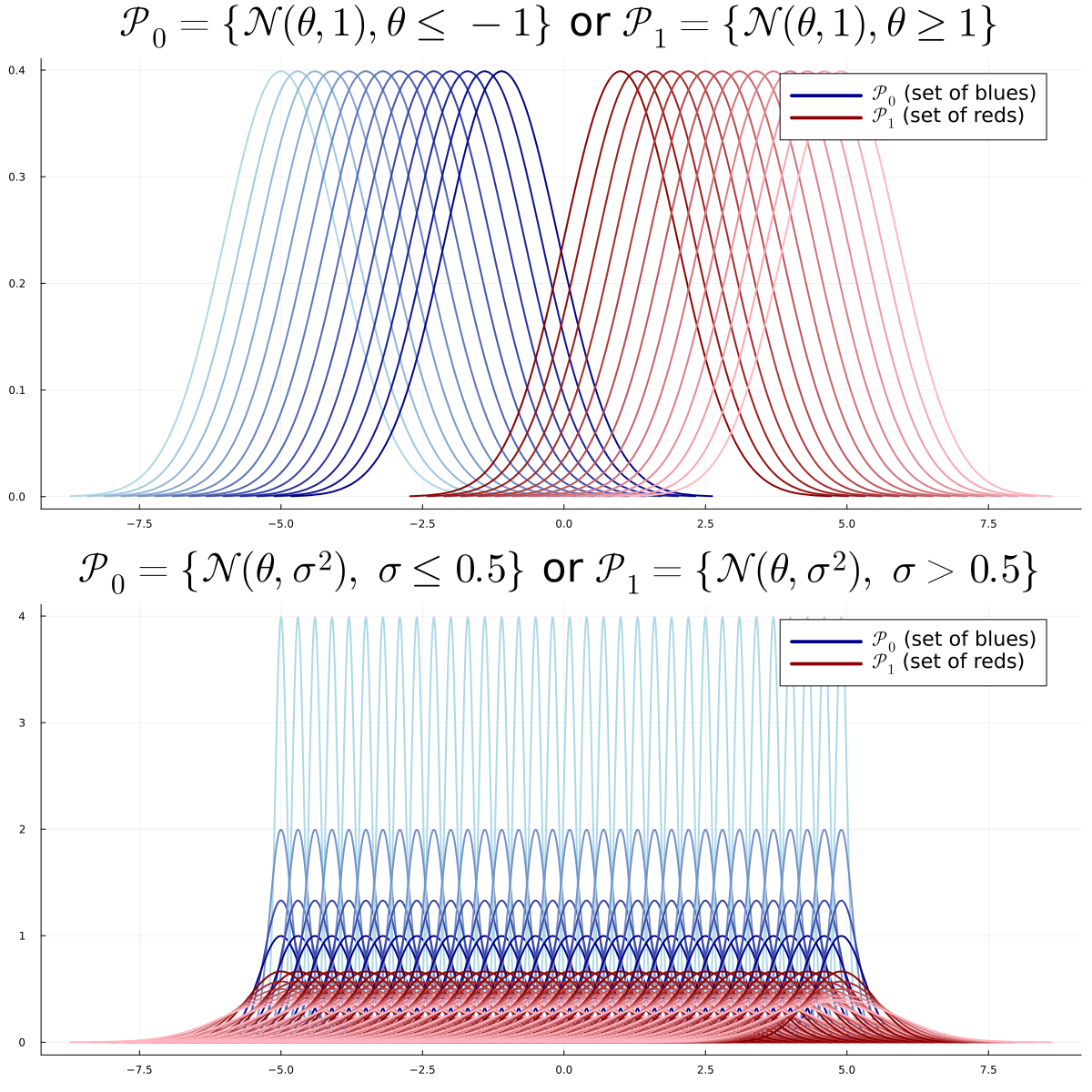

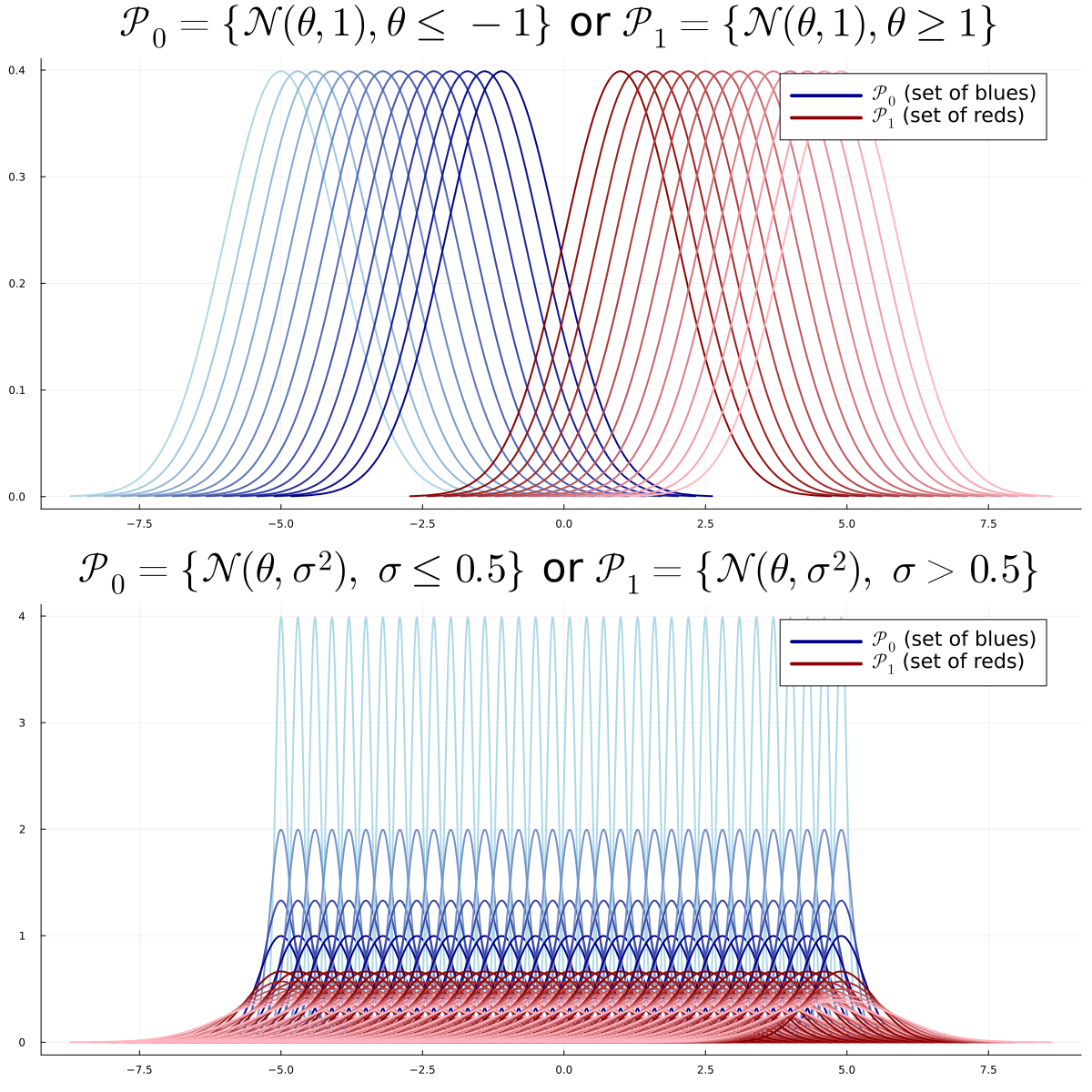

Two sets of distributions \(\mathcal P_0\), \(\mathcal P_1\)

Parameterized by disjoints \(\Theta_0\), \(\Theta_1\) \[ \begin{aligned} \mathcal P_0 = \{P_{\theta} : \theta \in \Theta_1\}, ~~~~ \mathcal P_1 = \{P_{\theta} : \theta \in \Theta_1\}\; . \end{aligned} \]

\(\exists \theta \in \Theta_0 \cup \Theta_1\) such that \(X \sim P_{\theta}\)

Goal: decide between \[H_0: \theta \in \Theta_0 \text{ or } H_1: \theta \in \Theta_1\]

Estimation

Test

Type of Problems

- Simple VS Simple:\[\Theta_0 = \{\theta_0\} \text{ and } \Theta_1 = \{\theta_1\}\]

- Simple VS Multiple:\[\Theta_0 = \{\theta_0\}\]

- Else: Multiple VS Multiple

Simple VS Simple

Multiple VS Multiple

Parametric VS Non-Parametric

- Parametric: \(\Theta_0\) and \(\Theta_1\) included in subspaces of finite dimension.

- Non-parametric: otherwise

Example of multiple VS multiple parametric problem:

- \(H_0: X \sim \mathcal N(\theta,\sigma)\), unknown \(\theta < 0\) and unknown \(\sigma > 0\): \(\Theta_0 \subset \mathbb R^2\)

- \(H_1: X \sim \mathcal N(\theta,\sigma)\), unknown \(\theta > 0\) and unknown \(\sigma > 0\): \(\Theta_1 \subset \mathbb R^2\)

Decision Rule and Test Statistic

A decision rule or test \(T\) is a measurable function from \(\mathcal X\) to \(\{0,1\}\): \[ T : \mathcal X \to \{0,1\}\; .\]

It can depend on the sets \(\mathcal P_0\) and \(\mathcal P_1\)

but not on any unknown parameter.

a test statistic \(\psi\) is a measurable function from \(\mathcal X\) to \(\mathbb R\): \[ \psi : \mathcal X \to \mathbb R\; .\]

It can depend on the sets \(\mathcal P_0\) and \(\mathcal P_1\)

Rejection Region

- For a given test \(T\), the rejection region \(\mathcal R \subset \mathbb R\) is the set \[\{\psi(x) \in \mathbb R:~ T(x)=1\} \; .\]

- Example of \(\mathcal R\), for a given threshold \(t>0\), \[ \begin{aligned} T(x) &= \mathbf{1}\{\psi(x) > t\}:~~~~~~\mathcal R = (t,+\infty)\\ T(x) &= \mathbf{1}\{\psi(x) < t\}:~~~~~~\mathcal R = (-\infty,t)\\ T(x) &= \mathbf{1}\{|\psi(x)| > t\}:~~~~~~\mathcal R = (-\infty,t)\cup (t, +\infty)\\ T(x) &= \mathbf{1}\{\psi(x) \not \in [t_1, t_2]\}:~~~~~~\mathcal R = (-\infty,t_1)\cup (t_2, +\infty)\; \end{aligned} \]

Recall of Proba

Consider a probability measure \(P\) on \(\mathbb R\).

- CDF (cumulative distribution function): \[x \to P(~(-\infty,x]~) = \mathbb P(X \leq x) ~~~~\text{(if $X \sim P$ under $\mathbb P$)}\]

Continous Measures

density wrp to Lebesgue: \(dP(x) = p(x)dx\)

PDF (proba density function): \(x \to p(x)\)

CDF: \(x \to \int_{\infty}^x p(x')dx'\)

\(\alpha\)-quantile \(q_{\alpha}\): \(\int_{\infty}^{q_{\alpha}} p(x)dx = \alpha\)

or \(\mathbb P(X \leq q_{\alpha} = \alpha)\)

Discrete Measures

- density wrp to counting measure: \(P(X=x) = p(x)\)

- CDF: \(x \to \sum_{x' \leq x} p(x')dx'\)

- \(\alpha\)-quantile \(q_{\alpha}\): \[\inf_{q \in \mathbb R}\{q:~\sum_{x_i \leq q}p(x_i) > \alpha\}\]

Examples

Gaussian/Bernoulli

- Gaussian \(\mathcal N(\mu,\sigma)\): \[p(x) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi \sigma^2}}e^{-\frac{(x-\mu)^2}{2\sigma^2}}\]

- Approximation of sum of iid RV (TCL)

- Binomial \(\mathrm{Bin}(n,q)\): \[p(x)= \binom{n}{x}q^x (1-q)^{n-x}\]

- Number of success among \(n\) Bernoulli \(q\)

Exponential/Geometric

- Exponential \(\mathcal E(\lambda)\): \[p(x) = \lambda e^{-\lambda x}\]

- Waiting time for an atomic clock of rate \(\lambda\)

- Geometric \(\mathcal{G}(q)\): \[p(x)= q(1-q)^{x-1}\]

- Index of first success for iid Bernoulli \(q\)

Gamma/Poisson

- Gamma \(\Gamma(k, \lambda)\): \[p(x) = \frac{\lambda^k x^{k-1}e^{-\lambda x}}{(k-1)!}\]

- Waiting time for \(k\) atomic clocks of rate \(\lambda\)

- Poisson \(\mathcal{P}(\lambda)\): \[p(x)=\frac{\lambda^x}{x!}e^{-\lambda}\]

- Number of tics before time \(1\) of an atomic clock of rate \(\lambda\)

Simple VS Simple

- We observe \(X \in \mathcal X=\mathbb R^n\).

- \(H_0: X \sim P\) or \(H_1: X \sim Q\).

- We know \(P\) and \(Q\) but we do not know whether \(X \sim P\) or \(X \sim Q\)

For a given test \(T\) we define:

- level of \(T\) = (type-1 error): \(\alpha = P(T(X)=1)\)

- power of \(T\) = 1 - (type-2 error): \(\beta = Q(T(X)=1) = 1-Q(T(X)=0)\)

| Decision | \(H_0: X \sim P\) | \(H_1: X \sim Q\) |

|---|---|---|

| \(T=0\) | \(1-\alpha\) | \(1-\beta\) |

| \(T=1\) | \(\alpha\) | \(\beta\) |

- unbiased: \(\beta \geq \alpha\)

- \(\alpha = 0\) for trivial test \(T(x)=0\) ! But \(\beta =0\) too…

Likelihood Ratio Test

- Test \(T\) that maximizes \(\beta\) at fixed \(\alpha\)?

- Idea: Consider the likelihood ratio test statistic \[\psi(x)=\frac{dQ}{dP}(x) = \frac{q(x)}{p(x)}\]

- We consider the likelihood ratio test \[ T^*(x)=\mathbf 1\left\{\frac{q(x)}{p(x)} > t_{\alpha}\right\} \;\]

- Equivalently, we can consider the log-likelihood ratio test: \[T^*(x)=\mathbf 1\left\{\log\left(\frac{q(x)}{p(x)}\right) > \log(t_{\alpha})\right\}\]

- \(t_{\alpha}\) is the \(\alpha\)-quantile of the distrib \(\frac{q(X)}{p(X)}\) if \(X\sim P\) \[ \mathbb P_{X \sim P}\left(\frac{q(X)}{p(X)} > t_{\alpha}\right) = \alpha\]

Neyman Pearson

The likelihood Ratio Test of level \(\alpha\) maximizes the power among all tests of level \(\alpha\).

Example: \(X \sim \mathcal N(\theta, 1)\).

\(H_0: \theta=\theta_0\), \(H_1: \theta=\theta_1\).

Check that the log-likelihood ratio is \[ (\theta_1 - \theta_0)x + \frac{\theta_0^2 -\theta_1^2}{2} \; .\]

If \(\theta_1 > \theta_0\), an optimal test if of the form \[ T(x) = \mathbf 1\{ x > t \} \; .\]

Proof of Neyman Pearson’s theorem

We prove the theorem in the case where \(P\) and \(Q\) each have a density \(p\) and \(q\) on \(\mathbb R^n\). For any \(t > 0\), define \[I_t(P, Q) = \int_{x \in \mathbb R^n} |q(x) - tp(x)|dx \; .\]

When \(t=1\), this quantity is equal to the total-variation distance between \(P\) and \(Q\). For any event A in \(\mathbb R^n\) , it holds that

\[ \begin{split} I_t(P, Q) &= \int_{x \in \mathbb R^n} |q(x) - tp(x)|dx \\ &= \int_{q(x)> tp(x)} q(x) - tp(x)dx + \int_{q(x)< tp(x)} tp(x) - q(x)dx\\ &= 2\int_{x \in \mathbb R^n} \mathbf1_{q(x)> tp(x)}(q(x) - tp(x))dx + t-1 \\ &\geq 2\int_{x \in \mathbb R^n} \mathbf 1_A \mathbf1_{q(x)> tp(x)}(q(x) - tp(x))dx + t-1\\ &\geq t-1 + 2(Q(A) - tP(A)) \; . \end{split} \]

If \(A = \{x \in \mathbb R^n : q(x) > tp(x)\}\), then the two last inequalities are equalities. In particular, \[I_t(P, Q) = t-1 + 2\sup_{A \subset \mathbb R^n}(Q(A) - tP(A))) \; .\]

Assume that the type-1 error of \(T\) is smaller than \(\alpha\): \(P(T=1) \leq \alpha\).

The power of \(T\), \(Q(T = 1)\), is upper-bounded as follows: \[ \begin{split} Q(T=1) &\leq Q(T=1) + t(\alpha - P(T=1))\\ &= \alpha t + Q(T=1) - tP(T=1) \\ &\leq \alpha t + \frac{t-1}{2} + \frac{1}{2}I_t \; . \end{split} \]

- There is equality in the second inequality if \(T=1\) is the event \(\{ \frac{q(X)}{p(X)} > t \}\).

- There is equality in the first inequality if \(P(T=1) = \alpha\).

Let \(t_{\alpha}\) be such that \(P(\frac{q(X)}{p(X)}> t_{\alpha}) = \alpha\). The test \(T^*(X) = \mathbf1 \{\frac{q(X)}{p(X)}> t_{\alpha}\}\) satisfies the two above points, since its rejection event is exactly \(\{T^*(X) = 1\} = \{\frac{q(X)}{p(X)}> t_{\alpha}\}\) and since \(P(T^* = 1) = \alpha.\) Hence, for any test \(T\) of type 1 error smaller than \(\alpha\), it holds that \(Q(T = 1) \leq Q(T^* = 1)\).

Examples

Example (Gaussians)

Let \(P_{\theta}\) be the distribution \(\mathcal N(\theta,1)\).

Observe \(n\) iid data \(X = (X_1, \dots, X_n)\)

\(H_0: X \sim P^{\otimes n}_{\theta_0}\) or \(H_1: X \sim P^{\otimes n}_{\theta_1}\)

Remark: \(P^{\otimes n}_{\theta}= \mathcal N((\theta,\dots, \theta), I_n)\)

Density of \(P^{\otimes n}_{\theta}\):

\[ \begin{aligned} \frac{d P^{\otimes n}_{\theta}}{dx} &= \frac{d P_{\theta}}{dx_1}\dots\frac{d P_{\theta}}{dx_n} \\ &= \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}^n}\exp\left({-\sum_{i=1}^n\frac{(x_i - \theta)^2}{2}}\right) \\ &= \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}^n}\exp\left(-\frac{\|x\|^2}{2} + n\theta \overline x - \frac{\theta^2}{2}\right)\; . \end{aligned} \]

- Log-likelihood ratio test:

- \(T(x) = \mathbf 1\{\overline x > t_{\alpha}\}\) if \(\theta_1 > \theta_0\)

- \(T(x) = \mathbf 1\{\overline x < t_{\alpha}\}\) otherwise

Example: Exponential Families

A set of distributions \(\{P_{\theta}\}\) is an exponential family if each density \(p_{\theta}(x)\) is of the form \[ p_{\theta}(x) = a(\theta)b(x) \exp(c(\theta)d(x)) \; , \]

We observe \(X = (X_1, \dots, X_n)\). Consider the following testing problem: \[H_0: X \sim P_{\theta_0}^{\otimes n}~~~~ \text{or}~~~~ H_1:X \sim P_{\theta_1}^{\otimes n} \; .\]

Likelihood ratio: \[ \frac{dP^{\otimes n}_{\theta_1}}{dP^{\otimes n}_{\theta_0}} = \left(\frac{a(\theta_1)}{a(\theta_0)}\right)^n\exp\left((c(\theta_1)-c(\theta_0))\sum_{i=1}^n d(x_i)\right) \; . \]

\[ T(X) = \mathbf 1\left\{\frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^n d(X_i) > t\right\} \;. ~~~~\text{(calibrate $t$)}\]

Example: Radioactive Source

The number of particle emitted in \(1\) unit of time is follows distribution \(P \sim \mathcal P(\lambda)\).

We observe \(20\) time units, that is \(N \sim \mathcal P(20\lambda)\).

Type A sources emit an average of \(\lambda_0 = 0.6\) particles/time unit

Type B sources emit an average of \(\lambda_1 = 0.8\) particles/time unit

\(H_0\): \(N \sim \mathcal P(20\lambda_0)\) or \(H_1\): \(N\sim \mathcal P(20\lambda_1)\)

Likelihood Ratio Test: \[T(X)=\mathbf 1\left\{\sum_{i=1}^{20}X_i > t_{\alpha}\right\} \; .\]

\(t_{0.95}\):

quantile(Poisson(20*0.6), 0.95)gives \(18\)

\(\mathbb P(\mathcal P(20*0.6) \leq 17)\):

1-cdf(Poisson(20*0.6), 17)gives \(0.063\)

\(\mathbb P(\mathcal P(20*0.6) \leq 18)\):

1-cdf(Poisson(20*0.6), 18)gives \(0.038\): reject if \(N \geq 19\)

Multiple-Multiple Tests

Generalities

\(H_0 = \{ \mathcal P_{\theta}, \theta \in \Theta_0 \}\) is not a singleton

No meaning of \(\mathbb P_{H_0}(X \in A)\)

level of \(T\): \[ \alpha = \sup_{\theta \in \Theta_0}P_{\theta}(T(X)=1) \; . \]

power function \(\beta: \Theta_1 \to [0,1]\) \[ \beta(\theta) = P_{\theta}(T(X)=1) \]

\(T\) is unbiased if \(\beta (\theta) \geq \alpha\) for all \(\theta \in \Theta_1\).

If \(T_1\), \(T_2\) are two tests of level \(\alpha_1\), \(\alpha_2\)

\(T_2\) is uniformly more powerfull (\(UMP\)) than \(T_1\) if

- \(\alpha_2 \leq \alpha_1\)

- \(\beta_2(\theta) \geq \beta_1(\theta)\) for all \(\theta \in \Theta_1\)

\(T^*\) is \(UMP_{\alpha}\) if it is \(UMP\) than any other test \(T\) of level \(\alpha\).

Multiple-Multiple Tests in \(\mathbb R\)

Assumption: \(\Theta_0 \cup \Theta_1 \subset \mathbb R\).

One-tailed tests: \[ \begin{aligned} H_0: \theta \leq \theta_0 ~~~~ &\text{ or } ~~~ H_1: \theta > \theta_0 ~~~ \text{(right-tailed: unilatéral droit)}\\ H_0: \theta \geq \theta_0 ~~~ &\text{ or } ~~~ H_1: \theta < \theta_0 ~~~ \text{(left-tailed: unilatéral gauche)} \end{aligned} \]

Two-tailed tests: \[ \begin{aligned} H_0: \theta = \theta_0 ~~~ &\text{ or } ~~~ H_1: \theta \neq \theta_0 ~~~ \text{(simple/multiple)}\\ H_0: \theta \in [\theta_1, \theta_2] ~~~ &\text{ or } ~~~ H_1: \theta \not \in [\theta_1, \theta_2] ~~~ \text{( multiple/multiple)} \end{aligned} \]

- Assume that \(p_{\theta}(x) = a(\theta)b(x)\exp(c(\theta)d(x))\) and that \(c\) is a non-decreasing (croissante) function, and consider a one-tailed test problem.

- There exists a UMP\(\alpha\) test. It is \(\mathbf 1\{\sum d(X_i) > t \}\) if \(H_1: \theta > \theta_0\) (right-tailed test).

Pivotal Test Statistic and P-value

Pivotal Test Statistic

- Consider \(\Theta_0\) not singleton. \(\mathbb P_{H_0}(X \in A)\) has no meaning.

\(\psi: \mathcal X \to \mathbb R\) is pivotal if the distribution of \(\psi(X)\) under \(H_0\) does not depend on \(\theta \in \Theta_0\):

for any \(\theta, \theta' \in \Theta_0\), and any event \(A\), \[ \mathbb P_{\theta}(\psi(X) \in A) = \mathbb P_{\theta'}(\psi(X) \in A) \; .\]

- Example: If \(X=(X_1, \dots, X_n)\) are iid \(\mathcal N(0, \sigma)\), the distrib of \[ \psi(X) = \frac{\sum_{i=1}^n \overline X}{\sqrt{\sum_{i=1}^n X_i^2}}\] does not depend on \(\sigma\).

P-value

See the (Pluto notebook: Illustration of pvalue)

We define \(p_{value}(x_{\mathrm{obs}}) =\mathbb P(\psi(X) > x_{\mathrm{obs}})\) for a right-tailed test.

For a two-tailed test, \(p_{value}(x_{\mathrm{obs}}) =2\min(\mathbb P(\psi(X) > x_{\mathrm{obs}}),\mathbb P(\psi(X) < x_{\mathrm{obs}}))\)

Under \(H_0\), for a pivotal test statistic \(\psi\), \(p_{value}(X)\) has a uniform distribution \(\mathcal U([0,1])\).

Proof.

The p-value is a probability, so it belongs to \([0,1]\). Let \(F_{\psi}\) be the cumulative distribution function of a random variable \(\psi(X)\) when \(X\) follows distribution \(P\), that is \(G_{\psi}(t) = \mathbb P(\psi(X) > t)\). It holds that \[ \mathbb P(\psi(X') > \psi(X) ~|~ \psi(X)) = F_{\psi}(\psi(X)) \] If \(u \in [0,1]\), then \[ \begin{aligned} \mathbb P(\mathrm{pvalue}(X) > u) &= \mathbb P(F_{\psi}(\psi(X)) > u) \\ &= \mathbb P(\psi(X) > F_{\psi}^{-1}(u)) \\ &= 1- F_{\psi}(F_{\psi}^{-1}(u)) = 1-u \end{aligned} \] Hence, \(\mathrm{pvalue}(X)\) is uniform when \(X\) follows distribution \(\mathbb P\). \[\tag*{$\blacksquare$}\]

- In practice: reject if \(p_{value}(X) < \alpha = 0.05\)

- \(\alpha\) is the level or type-1-error of the test

- Illustration if \(\psi(X) \sim \mathcal N(0,1)\) under \(H_0\):